Chapter 1: Presence¶

Introduction¶

In this first chapter, we will talk about the scientific world view that emerged as a result of the invention of the microscope. We will see that this had a profound impact of the way we percieve the arts and how we think about truth, the world, and ourselves. All this leads to the notion of man as a detached observer, that we humans grasp external reality through internal representation (Dreyfus and Taylor, 2015, p.2).

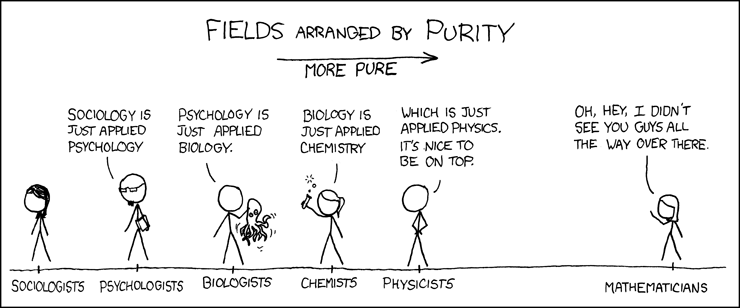

All this has led to a worldview in which only scientific knowledge is real knowledge – knowledge in which the role of the human observer or participant is abstracted away en that only states something about facts. The more abstract, the better the science and its resulting knowledge is, as is nicely illustrated by this little comic by xkcd:

This scientific metaphysics makes a sharp distinction between things of the mind and things of the world – a distinction whose roots can be traced back to Descartes. Things of the first category are individual, private, emotional, subjective and should not (according to this metaphysics) play any role in real, scientific discourse about how the world really is.

By stating that personal, emotional and subjective feelings are only things of the mind we can conclude that those kind of feelings occur only in the mind – that our sense of self, our sense of presence is located in our mind. By seeing, as Descartes did, our sense organs as transducers of stimuli to our brain and from their to our mind, we open the possibility of replacing these sense organs with (technological) artifacts that transduce the same things – or different things. In this metaphysics, we can imagine our sense organs being completely replaced by something else, which would give us a completely different sense of presence.

There are literary tons of examples (both in philosophy as in popular culture) that dwell on this notion of disembodied presence. One could think of, of course, the Matrix franchise (Wachovski, 1999), less well known and even better is the movie Strange Days (Bigelow, 1995). In this movie, cerebral activity can be recorded while an activity takes place; this provides a mean by which the experience can be re-experienced by someone else:

Session¶

During the sesion, we will use examples from art and philosophy to make a point that our sense of presence is fundamentally embodied, and that the introduction of a strict dichotomy between mind and world is unfeasable in the end. Even if it were possible to replace the sense organs with technological artifacts, we would still not be only mind: not only will at least those artifacts have a physical manifestation, but we still would need some bodily experience in order to make sense of what those transducers are transducing.

All this leads to the idea of the corporeality of knowledge: the view that real knowledge is not only abstract scientific knowledge, but that also bodily subjective knowledge can appeal to real-ness. This is especially the case when we are coping in a skillfull manner with the tools we use in order to do our daily labour.