A few days ago a student inquired about my definition of beauty. Initially, I responded that I don’t do semantics, and that I don’t entertain a definition of beauty – as much as I cannot give a definition of a table, or beer for that matter. But then we got talking…

Beauty as a common property of things

Looking from a linguistic point of view, ‘beautiful’ appears to be on a par with other adjectives such as red or heavy or righteous. However, beauty plays a different language-game than the other ones in that it seems to be telling us something about effect the thing under consideration has on us instead of a (more or less inherent) property of that thing. A chair or a hammer can be red or heavy, but neither can be righteous (if not in a metaphorical sense); a thought or a decision can be righteous, but neither can red or heavy (if not metaphorical – and even then I’m unsure about the redness of a thought or decision). But saying that a hammer or a chair or a thought or a decision is beautiful seems to impart a statement on a specific literal quality of either of those; it is a statement about the effect this ‘thing’ has on us, about the way we appreciate it – and in a sense the beauty of the hammer is comparable to the beauty of the thought or the decision.

A person can be beautiful, as can a landscape, a piece of music, a movie, or a book. Even inherent functional stuff such as a beaker or even a piece of computer code can appear beautiful, for those open to it. It appears that we can find beauty in almost anything (even though it has been the explicit domain of the beaux-arts since the sixteen-hundreds, but that is actually the subject of a next blog-post), and that all these beautiful things have something in common, viz. beauty. However, we will be hard pressed to explain to someone else why we find a particular landscape beautiful or a particular piece of music horrible. We cannot point to specific features of that landscape or that piece of music and say “you see? That’s what makes this beautiful.” There are no rules governing our judgement of beauty, as Kant has rightly point out; and nothing we say will convince our audience of the beauty of something that they find terrible.

A promise of happiness

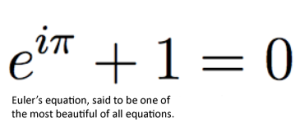

One of the common propensities of beautiful things is that we like to interact with them, be in their present, visit and revisit them. Their beauty is also – though not exclusively – their ability to deliver a certain sense of well-being, to elevate us from the quotidian hassle, to make us aware of ourselves while at the same time diminishing our own importance. Their beauty makes us gravitate towards them; it opens in us a certain curiosity, a desire to understand what it is. Beautiful things, says Alexander Nehamas, “spark the urgent need to approach, the same pressing feeling that they have more to offer, the same burning desire to understand what that is.” (Nehamas 2010, 73). We like to walk the Waddenzee at low tide, to listen to the Goldberg Variations, or to contemplate on Euler’s equation, because that what they have to offer is never quite exhausted by our experience of them. We know them, but they keep surprising us – sometimes in detail, sometimes as a whole. This seems to account for the fact that once a thing ceases to surprise us, it ceases to be beautiful (even though it can regain its attractiveness, if only on sentimental grounds; e.g. when you hear a once favourite tune after having shelved it years ago).

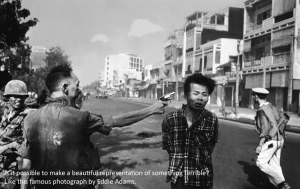

Beautiful things thus offer a promise of happiness, wrote Stendhal. This seems to be true even when things make us contemplative or dreary. Watching the rather gloomy film Full Metal Jacket, or listening to the dark music of Joy Division, can make us happy in a sad way; as long as it resonates with our own feeling of gloominess or darkness, as long as it means something to us. We are happy that the things we find important are rendered beautifully in film, in music, in art. This explains why things can be beautiful even if they display terrible things. The beauty of Schindler’s List or of the photographs of Eddie Adams does not lie in their accurate portrayal of their subject. As Hegel has already point out, such a correspondence-theory of beauty would reduce any discussion on beauty to a qualitative measurement of the exactitude of the depiction – making content and meaning irrelevant. The beauty of Spielberg’s or Adam’s works must be sought in the happiness (in the broadest sense possible) that they offer us, in their meaning-bringing potential, in their resonance with our mood – what, according to Nietzsche, constitutes the profound metaphysical import of the beautiful.

Beautiful things thus offer a promise of happiness, wrote Stendhal. This seems to be true even when things make us contemplative or dreary. Watching the rather gloomy film Full Metal Jacket, or listening to the dark music of Joy Division, can make us happy in a sad way; as long as it resonates with our own feeling of gloominess or darkness, as long as it means something to us. We are happy that the things we find important are rendered beautifully in film, in music, in art. This explains why things can be beautiful even if they display terrible things. The beauty of Schindler’s List or of the photographs of Eddie Adams does not lie in their accurate portrayal of their subject. As Hegel has already point out, such a correspondence-theory of beauty would reduce any discussion on beauty to a qualitative measurement of the exactitude of the depiction – making content and meaning irrelevant. The beauty of Spielberg’s or Adam’s works must be sought in the happiness (in the broadest sense possible) that they offer us, in their meaning-bringing potential, in their resonance with our mood – what, according to Nietzsche, constitutes the profound metaphysical import of the beautiful.

This import of the beautiful comes to the fore when we compare our aesthetic judgements to that of others. As Kant has observed, my aesthetic judgements are subjective but at the same time appeal to general validity. Even though I acknowledge the fact that not everybody shares my approbation of the novels by Céline or the fonts of Lucas the Groot (or, on the other hand, my dislike of the music of Anouk or the novels of J.K.Rowling), such a disagreement strikes me as personal attack. The beauty of something is not the same as the redness or the squareness of something – a property that can be checked by anyone who bothered to look. Someone, wrote Mary Mothersill “who finds nothing remarkable in what I find beautiful would strike me as slightly defective – as if something blocked his perception or impaired his sensibility”. What I find beautiful goes a long way into explicating what I find meaningful or important. It tells me, to paraphrase Heidegger, what is holy and what profound, what is weak and what is strong, what is just and what unjust.

This import of the beautiful comes to the fore when we compare our aesthetic judgements to that of others. As Kant has observed, my aesthetic judgements are subjective but at the same time appeal to general validity. Even though I acknowledge the fact that not everybody shares my approbation of the novels by Céline or the fonts of Lucas the Groot (or, on the other hand, my dislike of the music of Anouk or the novels of J.K.Rowling), such a disagreement strikes me as personal attack. The beauty of something is not the same as the redness or the squareness of something – a property that can be checked by anyone who bothered to look. Someone, wrote Mary Mothersill “who finds nothing remarkable in what I find beautiful would strike me as slightly defective – as if something blocked his perception or impaired his sensibility”. What I find beautiful goes a long way into explicating what I find meaningful or important. It tells me, to paraphrase Heidegger, what is holy and what profound, what is weak and what is strong, what is just and what unjust.

The social workings of beauty

This means that what I find beautiful drives me towards other people that are of the same opinion. We can imagine our best friends disliking some of the things we find beautiful, but a group of people who disagree on any and all aesthetics questions will probably lack any social cohesion. People who find a certain kind of music and attire beautiful will be hard pressed to interact in an intimate way with people that find this music and attire appalling. Contrary to what some believe, beauty is not purely subjective. It is, as Nehamas writes, “essentially social: it literally does create a new society. […] The judgement of taste has an inescapable social dimension” (77):

The interaction with others the judgement of taste requires prevents it from being purely subjective or private. My aesthetic judgments literally determine the course of my life, directing me to other people, other objects, other habits and ways of being. The judgment of beauty is essentially social […]. (85)

What we find beautiful determines the direction of our lives. The promise beauty offers points to our future, the people and surroundings we feel comfortable with. If Bernhard Stiegler is right is stating that knowledge is manifest first and foremost in beauty, then even our current scientific and technological society is only a manifestation of of our aesthetic judgements. Beauty is part of the everyday world of purpose and desire, history and contingency, subjectivity and incompleteness. “That is the only world there is, and nothing, not even the highs of the high arts, can move beyond it.” (35)

Reference

Nehamas, A., 2010, Only a Promise of Happiness. The Place of Beauty in a World of Art. Princeton.

Nynke